Tuesday evening, the baby was not kicking. She had not kicked in about nine hours, and April was growing concerned. She tried a warm bath, a sugary drink, a cold drink, a Mountain Dew, walking, sitting still, lying down, and playing music. We called her obstetrician’s office in Savannah; the answering service attendant and I strongly disagreed over whether she needed to know precisely what medicine April took at age six. (“I cannot tell you that right now.”/”Let me just write down that you refused.”/”Please make sure you also write down that we are two hours away and the baby is not moving.”) My truculence was punished by my not getting to talk to the doctor, though the secretary did condescend to say, “He said you can go to the Waycross ER.”

Tuesday evening, the baby was not kicking. She had not kicked in about nine hours, and April was growing concerned. She tried a warm bath, a sugary drink, a cold drink, a Mountain Dew, walking, sitting still, lying down, and playing music. We called her obstetrician’s office in Savannah; the answering service attendant and I strongly disagreed over whether she needed to know precisely what medicine April took at age six. (“I cannot tell you that right now.”/”Let me just write down that you refused.”/”Please make sure you also write down that we are two hours away and the baby is not moving.”) My truculence was punished by my not getting to talk to the doctor, though the secretary did condescend to say, “He said you can go to the Waycross ER.”

The Waycross ER it was.

Like most ERs, our ER is sometimes a place where you have to consider pinching your children to make sure they wail louder than the drug seekers. Last night, when we walked through the door, the lobby was calm, but they were training a sweet new intake clerk. If you are a waitress in training, spill a coke on me; I won’t say a word. A slow, new cashier? Count that money three times–I’ll wait. Kind and fumbly ER typist? No. I can’t.

I used my Teacher Voice to holler to a triage nurse: “How long’s it going to take to get this baby’s heartbeat seen about?” She asked if April was over twenty weeks, and then gave us the “Get Out of the Waiting Room Free” card: pregnant women over twenty weeks get to go straight to the third floor.

Three nurses greeted us quickly; it was a slow night. One patient had just given birth and was immediately moved to another wing: we then had the entire labor and delivery wing to ourselves. They set about trying to hear Stephanie Grace’s heartbeat using a fetal monitor; it seemed to be there, but faint. They weren’t sure, and wanted to do a sonogram–an expense we wanted to avoid if possible. But sitting there together on that hospital bed, not really knowing whether that was the baby’s heartbeat or an echo of April’s, we decided that one more scan might be best.

I have never seen a stiller sonogram.

I gripped April’s arm too tightly, willing the baby to wake. Once again, I was stunned by my inability to see anything baby about the sonogram. No heartbeat, no feet, no head, no arms. Just spine. It was March 16th all over again–but worse. I looked at the tech and the nurses, trying to sense weakness: who would tell us now? Did we really have to wait an hour and a half for a radiologist in Minnesota or Maine to download and read what looked instantly obvious? They formed a tight huddle, but as April went into the restroom, I pounced, hissing their names and making thumbs up and thumbs down motions with raised eyebrows. Demanding. Now.

I honor their professionalism. None cracked. But in my eighteen years teaching teens, I have learned to read split-second reactions. And although I wasn’t told, although no one’s face changed an iota, I knew.

April did, too. She swaddled herself in blankets and said, “I just don’t feel good about this. I don’t think I saw a heartbeat on the sonogram. Nothing moved.” We sat in silence, and time passed. The nurses and the tech once again entered in a huddle–they took turns speaking, so that no one person broke our hearts. There was no heartbeat.

At 46, my rage, I know is impotent. It will not pay the bills, fix the car, cure the cancer, or start my grandchild’s heart. It’s useless, really, to argue about what we are dealt--but I had continually prayed, hoped, and believed for Stephanie Grace to have a chance to enjoy a few hours on earth. To ask April to gracefully bear this, too, seemed a most brutal injustice.

April’s tears were hard and angry, but brief–because, as she points out, “I was given medicine.” As she dozed, I sat wondering about the unfolding day–we’d envisioned Stephanie Grace’s birthday as a summer day in a Savannah hospital with a top-notch neonatal unit. To be in small-town Waycross on a spring work day was unexpected. I knew the day would be long, but I hoped we would be able to proceed with what April wanted–very few visitors, a tight circle of love around sweet Stephanie Grace.

The first sign that the day held possibility: a message brightened my phone about 7:00 AM. “I’m working in the OB today if you need me. I love you.” A former student, Ursy, was checking in. Her firstborn also died from severe birth defects, and she and April had been planning to have lunch one day and discuss what April could expect. A room-brightener by nature, she cheered us greatly. She told us the story of her daughter’s birth; the girls discussed memorial tattoos–April wanted Stephanie Grace’s footprints and the green anencephaly ribbon. Ursy kept telling April, “Get lots of pictures. Lots and lots of pictures!”

Pictures posed a problem: early that morning, we’d learned that the photographer we planned to use was unavailable on such short notice; others were similarly booked or not up to the task–and who could blame them, with so much unknown? It was anguishing–it was so important to us all that this day be preserved. We’d been comforted by others’ beautiful baby pictures, and April wanted her own. I kept Facebooking photographers, and finally texted another former student, “Help me find someone!” Within thirty minutes, a sweet-voiced stranger named Stacey was reassuring me, “I’m on my way,” and another piece of our day fell into place.

In all of our time enduring medical crises and hospitalizations, I have learned two things: the first is that the right person will ALWAYS show up. I was mildly curious who the day’s right person would be. For us, the Right Person is never a best friend or a favorite relative because second truth is simply emotional distance is ideal in a hospital visitor during the first throes of crisis. (Alternately: helpful acquaintances can be better than friends, who are often better than family.) This second truth seems cold, but it’s a truth we have lived. It is easy to lose yourself to sorrow when a much-loved aunt shows up, especially if her emotions are also running high. A casual friend or coworker can be a more appropriate support; they recognize your sadness,but their presence encourages equilibrium, something a 40-hour stretch without sleep can require.

At 9:35, a Facebook message came through: “I’m wrapping up things here at the church so I can be free for you the rest of the day.” And, just like that, I knew who the Lord had planned to be the day’s right person: Beth, the mother of four of my former students. I’d seen her at a restaurant a few weeks before and told her the news; she invited April to lunch and took her shopping for the baby. And she planned to attend Stephanie Grace’s sad, sweet birthday.

April dozed as the baby’s father slept in a recliner, having come straight from the night-shift. I quietly sent texts to family members, including Abby, who reported that Greg was still asleep after his midnight run to check on us in the ER. I advised her to wake him and arrive by 11:00.

By 11:17, we’d assembled–a small, slightly frightened crew. The nurses had cautioned that the baby, having died, may be discolored or disfigured; they explained privately to me that, for babies like Stephanie Grace, if the baby’s defect was thought too gruesome for the mother to see, the nurses would whisk the child out of the room and “attempt to make the baby presentable, or wrap her so that the mother can at least see the hands and feet.” We all were silently afraid of what we might see, of what the next hours held.

Abby, Beth, and Stacey waited together down the hall as April slept. We’d been told that the mothers of stillborn, preterm babies often slept, then woke abruptly and–whoosh!–gave birth before the nurse call button could even be pushed. As April slept, my prayers were frantic. My mind was frantic. I could not deliver my granddaughter, could not disentangle her from the sheets. Surely that would not be required of me.

(Author’s note: Brown text below may be difficult to read, but no harder than it was for us to live.)

And then it was time. April awoke, and the just-in-time doctor delivered sweet Stephanie Grace at 12:13–and I was overtaken. Ninety seconds before, I doubted my ability to look at my granddaughter, but I was now thunderstruck, mesmerized. The nurses were hastening her from the room, and I whipped behind them, literally, completely unable to take my eyes from this perfectly imperfect, tiny child.

“Don’t you want to stay and encourage April?” a sweet nurse suggested, for the defect was horrific. “No, I’m not leaving her side,” I replied, my eyes still fixed on her. Two truths: It was so awful. And she was so beautiful. They took Stephanie Grace to a nearby room and laid her on an empty hospital bed. As she lay on the blue plastic chuck, her perfect mouth open and her tiny hands clasped, I saw what will be the horror of my life–a secret the sonogram had not revealed: the baby was missing her right leg below the knee. My brain screamed and screamed and screamed at God: ALL April had come to want was a footprint tattoo, and she couldn’t even have THAT??? Two feet was too much to ask for? We were to be denied even that???

And then, that quickly, the rage was gone–I knew we would have loved her, leg or no leg. We would have played soccer, gone to therapy, visited specialists–the rage was gone and the wishing returned. I so desperately wanted a well, one-legged soccer player romping through our house. I wanted the hassle of driving to the best pediatric orthopedists.

My breath was gone; I was full of wanting. I was only all the wanting in the world.

I started taking pictures of the baby, ungroomed, imperfect, untouched. I turned my camera into a sanctuary forever–full of true, if gruesome beauty. She had one leg, a clubbed hand, a deformed arm, and no skull–but also long fingers, a sweet face, a tiny nose, and decidedly un-toadlike eyes (how wrong the doctor had been!)–all of her, unswaddled. Pristine.

Greg came in search of me, and after begging him not to leave the baby for a second, I went to April. She was proud–radiant with pride. I went to get the photographer and Abby–who went immediately to the baby, and then to tell her sister of Stephanie Grace’s beauty. To soothe her as only a sibling can, to say, you will be able to hold and love this baby because she so very far from frightening.

April stuck her hand out, silently demanding my iPhone. She saw the baby’s hands and relaxed some. The baby’s face, her small nose. April relaxed futher, and a flick of her wrist got her more quickly to the other pictures. She brought the iPhone to her face, peering and scrutinizing. I could almost hear her saying to herself, “That’s not too bad.”

And suddenly, holding her baby became possible for her.

The nurses dressed Stephanie Grace in a tiny gown and covered her head in two caps; they wrapped her in a pink lace-trimmed blanket hand-sewn by an 83 year-old woman touched by April’s story. Stephanie Grace, snug and beautiful, was taken down the hall to her mother’s arms.

The only word: transformation. The truth of that word, of every word here–all of the Unknown that had stalked and savaged us for weeks was gone. Removed. East and West became real–the Unknown was so far away and so absurd. The room was reverent–this sounds like hyperbole and romance and overkill, but oh, I assure you, it is so true–the room was far and away and time was frozen and sound was still and there was just that baby, that sweet baby, and all of these people who loved her.

It was so awful, so beautiful. So terrible, so holy.

She was our shared treasure, everyone holding her and studying her, marveling at her pin-prick fingernails, and April adoring her tiny ears. Her petite mouth was a mirror of April’s. We held her hands, kissed her forehead. There was no chatter or cooing–looking back, there is so much silence, but there was no need for words. The cries of you’re here and I’m delighted and you’re here, and I’m so sorry, though unspoken, filled the room.

We took so many pictures. The compulsion: capture every instant. Store it up. True treasure. Truth and treasure. The room was filled with these two things. There was no posing, no checking for a camera, no glancing or glimpsing.I did not look at April, Abby, or Greg–I did not worry about any of them. There was no concern for anyone or anything–our time in that room was the most singular time in our lives. We were all alone, so alone with that sweet baby. Her nineteen ounces filled all space.

We held Stephanie Grace throughout the afternoon. At 3:00, the nurses suggested making a pallet for the baby on the sofa, so April could see her from her bed. I told Stephanie good-bye, once, then twice, and, in order to live, I have to know she heard my apologies as well. They are legion.

***************

There is so much that we do that is wrong and ill. We make decisions and say words that are foolish and hateful. We destroy ourselves with anger and rage and all sorts of envy. We self-destruct and immolate and blaze and blaze and blaze. There is so much wrong. There is so much wrong in all of us.

But I have seen the right, and I have seen the perfect. I have glimpsed the glory, and I will tell the tale.

***************

As she went to sleep empty-armed and aching in her hospital bed last night, April said to me through the darkness, “I know this sounds crazy, but I’d do it all again.”

As would we all.

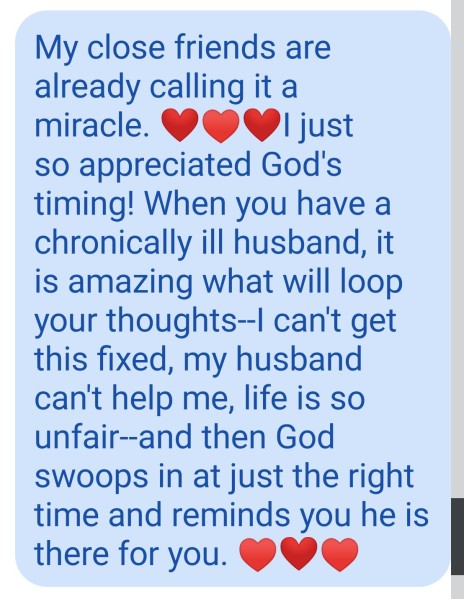

Last Saturday, I went to the mall, and as I was leaving, I bumped into a former student and her mother. They are the kindest of people, and I was wild-eyed and sad–it was just sixteen days from my father’s death by suicide and thirty-six hours before my husband’s second heart surgery in eight weeks. It was just too much, and they could tell.

Last Saturday, I went to the mall, and as I was leaving, I bumped into a former student and her mother. They are the kindest of people, and I was wild-eyed and sad–it was just sixteen days from my father’s death by suicide and thirty-six hours before my husband’s second heart surgery in eight weeks. It was just too much, and they could tell. near-miss, and Greg was back on restrictions–couldn’t lift, couldn’t drive. I lay in bed until 11:00 AM then forced myself to do chores. Our normally tidy house was no longer so–I couldn’t do it all: work, grade, tutor, exercise, cook, and clean. I vacuumed, noting that somehow the antique marble coffee table was in the middle of the rug. I washed sheets and the duvet cover, going outside midway through the drying cycle to ensure that the duvet was not eating the sheets, not wanting to deal with that.

near-miss, and Greg was back on restrictions–couldn’t lift, couldn’t drive. I lay in bed until 11:00 AM then forced myself to do chores. Our normally tidy house was no longer so–I couldn’t do it all: work, grade, tutor, exercise, cook, and clean. I vacuumed, noting that somehow the antique marble coffee table was in the middle of the rug. I washed sheets and the duvet cover, going outside midway through the drying cycle to ensure that the duvet was not eating the sheets, not wanting to deal with that.

This blog was originally a Facebook note on September 19, 2009. (Today I found myself writing part two, so I thought I would post this, part one, tonight.)

This blog was originally a Facebook note on September 19, 2009. (Today I found myself writing part two, so I thought I would post this, part one, tonight.) the teetotaler and the gal who enjoyed the glass of good merlot, the mother whose kids were bedraggled and barefoot and the mom whose kids wore matching Crocs with their every outfit. I exasperated her with my total cluelessness about the feminine world of makeup and hair: “You send that child over HERE before that dance recital. Don’t you TOUCH her hair.” Steph was my girls’ biggest fan, and the stars in their eyes were certainly those that I expected.

the teetotaler and the gal who enjoyed the glass of good merlot, the mother whose kids were bedraggled and barefoot and the mom whose kids wore matching Crocs with their every outfit. I exasperated her with my total cluelessness about the feminine world of makeup and hair: “You send that child over HERE before that dance recital. Don’t you TOUCH her hair.” Steph was my girls’ biggest fan, and the stars in their eyes were certainly those that I expected.

Three months: that

Three months: that

When we were in Seattle in the spring of 2001 for my husband’s bone marrow transplant, we allowed our six-year old daughter to fly home to Georgia for her last week of first grade. (This was pre-9/11; also, it was a non-stop flight.) Before April boarded the plane, I was a sobbing, hysterical mess–Greg was faring very poorly at the time; he had

When we were in Seattle in the spring of 2001 for my husband’s bone marrow transplant, we allowed our six-year old daughter to fly home to Georgia for her last week of first grade. (This was pre-9/11; also, it was a non-stop flight.) Before April boarded the plane, I was a sobbing, hysterical mess–Greg was faring very poorly at the time; he had  Tuesday evening, the baby was not kicking. She had not kicked in about nine hours, and April was growing concerned. She tried a warm bath, a sugary drink, a cold drink, a Mountain Dew, walking, sitting still, lying down, and playing music. We called her obstetrician’s office in Savannah; the answering service attendant and I strongly disagreed over whether she needed to know precisely what medicine April took at age six. (“I cannot tell you that right now.”/”Let me just write down that you refused.”/”Please make sure you also write down that we are two hours away and the baby is not moving.”) My truculence was punished by my not getting to talk to the doctor, though the secretary did condescend to say, “He said you can go to the Waycross ER.”

Tuesday evening, the baby was not kicking. She had not kicked in about nine hours, and April was growing concerned. She tried a warm bath, a sugary drink, a cold drink, a Mountain Dew, walking, sitting still, lying down, and playing music. We called her obstetrician’s office in Savannah; the answering service attendant and I strongly disagreed over whether she needed to know precisely what medicine April took at age six. (“I cannot tell you that right now.”/”Let me just write down that you refused.”/”Please make sure you also write down that we are two hours away and the baby is not moving.”) My truculence was punished by my not getting to talk to the doctor, though the secretary did condescend to say, “He said you can go to the Waycross ER.”

Today, I awoke to a Facebook post. It said simply, “It’s a nice day for a white wedding,” and my heart just broke. The bride, Shelby, is young, beautiful, tough–and motherless.

Today, I awoke to a Facebook post. It said simply, “It’s a nice day for a white wedding,” and my heart just broke. The bride, Shelby, is young, beautiful, tough–and motherless.